For two weeks in late November 2025, Split quietly became one of the most densely populated “control rooms” in Europe. Sixty‑two participants from 26 nationalities gathered for the CERN Accelerator School (CAS) course on Beam Instrumentation. Between morning lectures, afternoon hands‑on sessions and late‑night discussions over the Adriatic, the school offered something that no digital training can fully reproduce: a living community of accelerator physicists learning, debating and imagining the next generation of machines together.

The head of the Beam Instrumentation Group, Thibaut Lefevre, and a member of the program committee for this course, came as a lecturer and hands-on expert. Ironically, Thibaut never attended a CAS course as a student. His first contact with CAS came in 2007, when, after years working at CERN, he was invited by then group leader Hermann Schmickler to develop a lecture on short electron bunch diagnostics for the afternoon courses. Since then, he has been a regular CAS lecturer in beam instrumentation and, for the 2025 edition in Split, he returned, coordinating with CAS and the program committee the design of a course with a curriculum rooted in fundamentals and aligned with the most recent challenges in the field.

“The fundamentals do not change very much,” he notes in the interview, “but the applications and technologies that push the boundaries of our field are constantly evolving.”

Beam instrumentation is sometimes described as the “eyes or the ears” of an accelerator: without it, operators are effectively blind. The Split programme reflects that central role, starting with measurement principles, time‑ and frequency‑domain signal analysis, and transverse and longitudinal beam dynamics, before moving on to detection techniques, timing and synchronisation, and machine protection. For Thibaut, this balance between foundations and frontier topics is deliberate. As Isaac Newton said, we, scientists, are “standing on the shoulders of Giants”, previous generations of physicists and engineers, and CAS has a responsibility to keep that lineage visible while exposing students to today’s state‑of‑the‑art. That is why the course mixes concept‑driven lectures with machine‑specific sessions on diagnostics for hadron synchrotrons and colliders, lepton linacs, FELs and future projects such as FCC‑ee.

Building a two‑week residential school means making hard choices: what to include, how deep to go, and how to keep coherence from the first coffee on Monday to the closing session two Fridays later. The 2025 BI course starts with a common language—basic measurement principles, signal analysis and beam dynamics—before opening into the core toolbox of any beam instrumentation specialist: BPM systems, tune and chromaticity measurements, emittance and bunch‑length diagnostics, and the chain from analogue front ends to digital processing.

The committee also wanted the timetable to mirror the diversity of real accelerator environments. Participants learn how diagnostics are adapted across hadron colliders, light sources, linacs and advanced accelerating techniques, and how collective effects, machine protection requirements, timing and synchronisation or real-time feedback shape instrument design. Machine learning applications in BI is a new addition to the program, signalling how data‑driven methods are becoming central to modern operations.

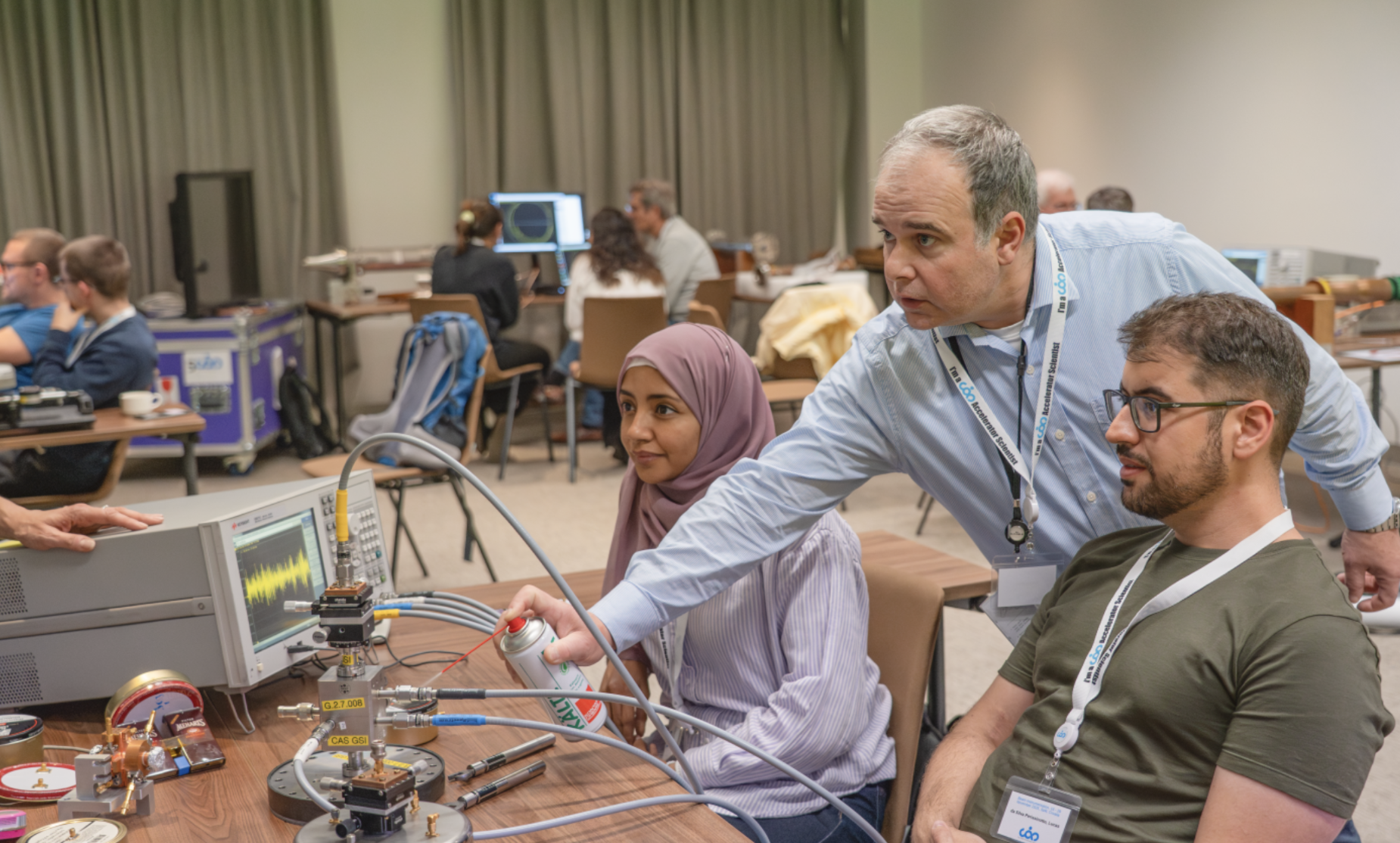

Hands‑on work is not an add‑on; it is a second backbone of the school. Students rotate through four practical blocks—BPMs, optical methods, RF and tune diagnostics—using dedicated software and hardware setups to move from theoretical slides to real‑world signals and analysis chains.

Posters, a one‑slide‑one‑minute session and structured discussion slots push them to synthesise what they learn and to articulate it to their peers and lecturers.

Ask Thibaut what makes CAS special, and he talks as much about people as about physics. From his perspective, lecturers learn almost as much as students: they sit in on each other’s talks, argue over details in coffee breaks and discover approaches from other labs that later feed back into their own systems. Over the years, he has seen former students reappear as collaborators at CERN, colleagues in national labs or experts leading instrumentation projects in light sources and universities around the world.

For participants, the impact will be seen as the course advances. Technically, an intensive schedule of 45–50 minutes lectures over two weeks compresses years of scattered learning into a coherent picture of the field. Socially, shared dinners, the excursion to Krka National Park and Šibenik, informal “CASaoke” or cinema evenings create bonds that outlive the school itself. For the school, social bonding is essential. As Thibaut notes, newcomers may initially feel overwhelmed by the density of information. Still, they return with a more precise map of beam instrumentation and a contact list that can unblock problems long after the last session in Split.

As we progress the interview with Thibaut, the conversation inevitably turns to proceedings. Far before setting foot at the school, some of the earliest accelerator books on his office shelf were CAS proceedings, and he keeps a personal “library” of them. For him, maintaining and updating this written record is part of CAS’s core responsibilities: the fundamentals remain stable, but the ways technologies extend performance, cope with higher intensities, or exploit new analysis methods need to be periodically captured.

All CAS proceedings are available online, and the Split edition will eventually join this lineage, with updated lectures and new chapters on topics such as machine learning in diagnostics and advanced timing systems. For young scientists entering the field, these proceedings often serve as both an introduction and a reference they return to throughout their careers.

By the time this article is published, the lecture hall overlooking the Adriatic will be quiet again, the poster boards dismantled, and the WhatsApp groups filled with farewell photos and promises of future visits. The participants will be back in control rooms, labs and universities, applying what they learned to real machines—from small university linacs to flagship facilities like the LHC and emerging projects in Europe and beyond.

Beam instrumentation may be about measuring beams with ever greater precision. Still, in Split in November 2025, it was also about something less quantifiable: transmitting a culture of collaboration, curiosity and shared responsibility for the accelerators that enable modern science.

As they say around here: Teamwork makes the beam work.